I. Introduction The tetrameric protein at left is Hemoglobin A in its oxygenated state, comprising two alpha (α) and two beta (β) globin chains, encoded by an α and β globin gene, respectively. Hemoglobin, the most efficient O2 carrier known, is found in very high concentrations within red blood cells of humans and nearly all other vertebrates. It is also present in a few invertebrates, dissolved directly in their blood. Oxygenated hemoglobin within red blood cells is responsible for ferrying oxygen acquired via gas exchange in the pulmonary capillaries of the lungs to cells throughout the body. The release of oxygen from hemoglobin provides these cells with adequate oxygen for cellular respiration and restores hemoglobin to a deoxygenated state. The structure of the hemoglobin protein and associated heme cofactors endows it with the remarkable ability to bind and release molecular oxygen (O2) under appropriate conditions. This exhibit is an introduction to hemoglobin structure-function relationships, the pathology of a type of Sickle Cell Disease that some mutations in the β globin gene can produce, and the molecular basis of carbon monoxide toxicity.

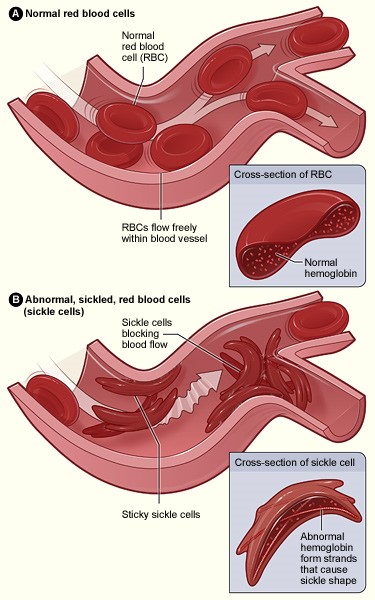

II. Tertiary Structure, Heme-mediated O2 Binding, and Cooperativity Each α and β subunit shares a conserved tertiary structure composed mostly of α helices. Two dimers ( α1β1 and α2β2) associate to form the tetramer. Each of the four Hemoglobin A subunits carries a planar heme cofactor, detailed here for one of the α subunits. The hemes are pigments that endow hemoglobin with its bright red color and its ability to bind and release oxygen. Each heme consists of a central iron atom (Fe) held in an aromatic, porphyrin ring. The Fe exists in a charged, ionized state, coordinated by four nitrogen atoms in the center of the ring. The Fe is anchored to a globin subunit by a coordinate, or dative, covalent bond to a histidine side chain, termed the F8 or proximal histidine. A coordinate bond occurs when one participating atom contibutes both shared electrons to a covalent bond. The F8 histidine is the 8th residue of the F helix in both α and β globin chains. O2 is reversibly bound by the heme Fe through a coordinate bond. O2 binding results in in an "end-on bent" arrangement: one oxygen atom binds to Fe and the other oxygen is seen to protrude at an angle. Another histidine residue, the E7 or distal histidine, is the 7th residue of the E helix and serves to stabilize bound O2. In a deoxygenated globin, a loosly sequestered H2O molecule takes the place of O2. Although hemoglobin can carry other gases, e.g. carbon dioxide and nitric oxide, these are not bound by the heme, but by side chains elsewhere in the protein. Upon binding O2 in the pulmonary capillaries of the lungs, where the partial pressure of oxygen is high, a globin monomer changes shape due to the movement of the heme Fe from a position slightly "below" the plane of the heme to a position in the heme plane. This draws the F8 (proximal) histidine toward the heme, as can be seen by alternating between an α subunit in its deoxygenated (DEOXY) and oxygenated (OXY) state. As the F8 histidine shifts, the entire F helix also moves, slightly altering the conformation of the globin monomer. Thus, an O2 binding event in one globin chain can generate an F8 histidine shift, F helix movement, and a subtle alteration of the subunit. This event can be amplified into a conformational change of the entire hemoglobin tetramer, which facilitates the binding of O2 by other subunits. The amplification is generated because the carboxy ends of the F helices that contain the F8 histidines of each globin subunit lie near the interface of the α1β1 and α2β2 dimers. As hemoglobin reaches tissues with lower O2 partial pressure and O2 is released, an OXY >> DEOXY conformational change of a single subunit is transmitted to the other tetramer subunits, altering tetramer structure and stimulating O2 release by other subunits. The remarkably efficient mechanism of oxygen uptake and delivery by hemoglobin is known as cooperative binding/release, and O2 can be considered an allosteric regulator of the hemoglobin tetramer. More information on hemoglobin cooperativity is available: see the cooperative binding popup. III. Hemoglobin and Sickle Cell Anemia Deoxy-hemoglobin is shown at left, with the two alpha and two beta chains highlighted and the hemes lacking bound oxygen. Like most other proteins in an aqueous, cellular environment, the Hemoglobin A tetramer has a preponderance of polar/charged amino acids at its surface, where their polar side chains can form weak bonds with polar water (H2O) molecules surrounding the soluble, globular protein (notes: H2O hydrogens are not shown, H2O oxygens are not shown to scale, and in vivo there would be many more H2O molecules surrounding the protein). However, there also exist some hydrophobic residues at or near the protein's surface. One small cluster of these hydrophobic residues forms a pocket on the surface of both globin β chains. These pockets play an essential role in the pathology of one form of Sickle Cell Disease, Sickle Cell Anemia (SCA), also known as HbS disease, as discussed below. A second feature of note that is relevant to understanding the molecular basis of SCA is a glutamic acid residue at position 6 of the β globin chains (GLU6). The structure at left shows two Hemoglobin tetramers that are "dimerized," representing the beginning of a chain of "polymerized" hemoglobin tetramers that can form long fibers or strands in the red blood cells of Sickle Cell Anemia (SCA) patients. The formation of these strands cause a deformation of the normally disc-shaped red blood cells into crescent-shaped ("sickled") cells that can lodge in small capillaries, thereby blocking blood flow and hence oxygen supply to peripheral tissues (see Figure 1, below). SCA can be a debilitating disease with symptoms of severe pain and long term tissue damage. Note that the two hemoglobin tetramers are linked by close contact of a β subunit from each, as elaborated below.

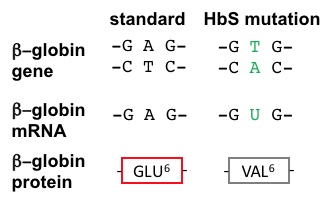

SCA Hemoglobin (Hemoglobin S) is caused by a mutant allele of the hemoglobin B gene (HbS). The HbS transversion mutation encodes a β subunit of hemoglobin with a hydrophobic valine at position 6 (VAL6) instead of the standard glutamic acid (GLU6): see above visualization and Figure 2, below. Since GLU6 is a surface amino acid, the HbS mutation results in a β subunit with a hydrophobic VAL sidechain instead of the normal polar GLU sidechain protruding from the surface of the protein, interacting with polar H2O molecules. Thermodynamically, this is an unfavorable state. Thus, the mutant VAL6 of a β subunit in one hemoglobin tetramer minimizes contact with solvent H2O by packing into a complementary hydrophobic surface pocket of a β chain of another hemoglobin tetramer, mentioned above. The hydrophobic "bonding" of mutant HbS subunits in Hemoglobin S tetramers drives the aggregation of hemoglobin monomers into long, insoluble hemoglobin fibers that deform red blood cells. This is the molecular basis of SCA. SCA is only one member of the Sickle Cell Disease family. Other SCDs are caused by different globin mutations.

Since each HbS beta globin subunit has a VAL6 and a complementary hydrophobic pocket, this affords the opportunity for mutant Hemoglobin S proteins to bind multiple partner tetramers, thus forming multi-stranded fibers that have a semi-helical structure (see Figure 3, below).

IV. Carbon Monoxide Toxicity As stated previously, hemoglobin can carry other gases besides oxygen. Carbon dioxide and nitric oxide are examples of gases that can be born by hemoglobin independent of heme cofactors. However, carbon monoxide (CO) binds to the Fe of hemoglobin's porphyrin hemes, directly competing with oxygen. This gas is highly toxic: hemoglobin's binding affinity for CO is ~200 times stronger than its affinity for oxygen! The extreme toxicity of CO lies in its ability to affect the quaternary structure of hemoglobin. Even at low partial pressures, CO binding by a single globin chain's heme can generate a shift in hemoglobin tetramer structure, greatly increasing other globin subunits' affinity for oxygen and preventing oxygen's release in peripheral tissues. Starving cells of oxygen accounts for CO's potential lethality.

V. References 1. Park, S.-Y., Yokoyama, T., Shibayama, N., Shiro, Y., Tame, J.R. (2006). 1.25 a resolution crystal structures of human haemoglobin in the oxy, deoxy and carbonmonoxy forms. J.Mol.Biol. 360: 690-701. 2. Harrington, D.J., Adachi, K., Royer Jr., W.E. (1997). The high resolution crystal structure of deoxyhemoglobin S. J.Mol.Biol. 272: 398-407. 3. Shaanan, B. (1983). Structure of human oxyhaemoglobin at 2.1 A resolution. J.Mol.Biol. 171: 31-59. 4. Berg JM, Tymoczko JL, Stryer L. (2002). Biochemistry. New York: W.H. Freeman. |

|||||||